What Happened

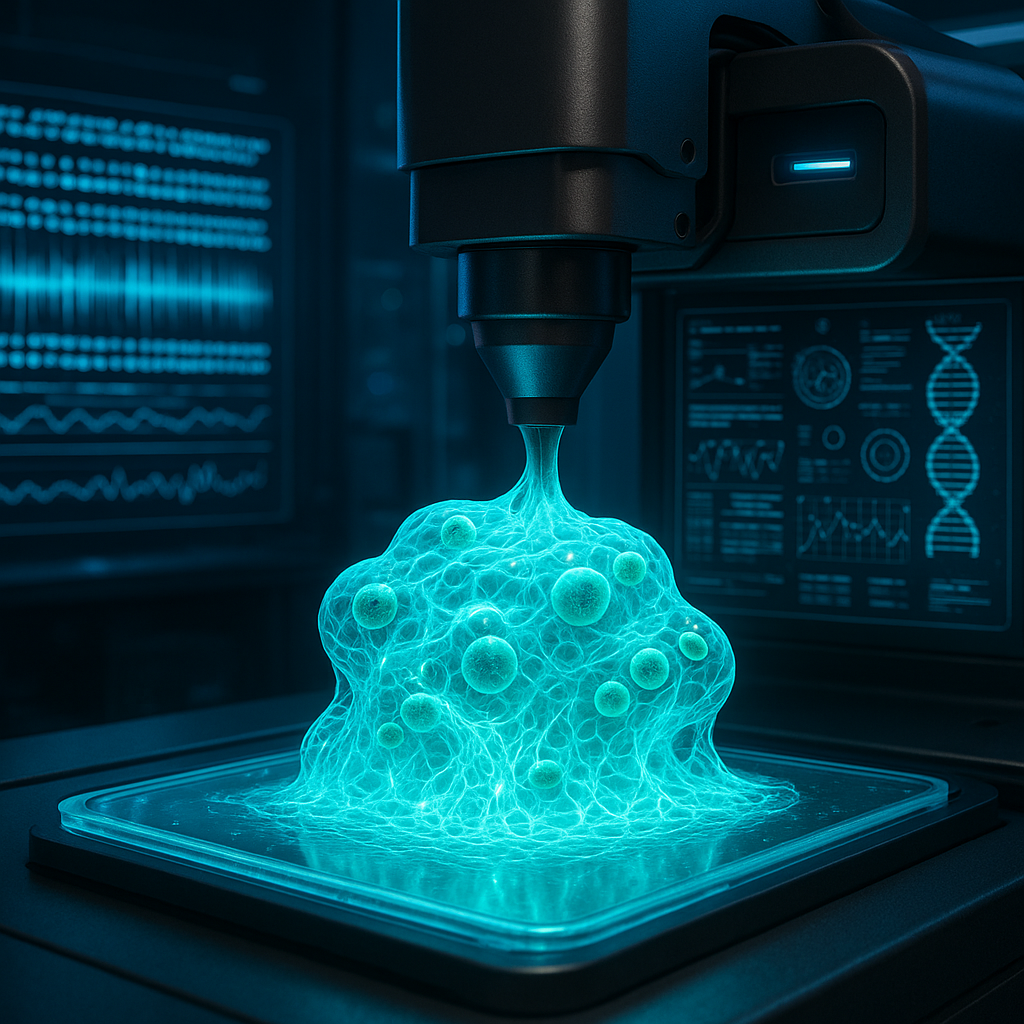

Researchers have developed a groundbreaking programmable microbial ink for 3D printing of living materials using genetically engineered protein nanofibers. Published in Nature in late 2021, this innovation introduces a novel biofabrication method where living cells embedded within a protein-based ink can be precisely printed into complex architectures. The microbial ink leverages genetically engineered bacteria to produce extracellular protein nanofibers that serve as the structural matrix, enabling the creation of living, functional materials with programmable properties.

Why It Matters

This development represents a significant leap in the integration of synthetic biology with additive manufacturing. Traditional 3D printing materials are inert, limiting their functionality to static shapes and mechanical properties. In contrast, living materials can respond dynamically to environmental stimuli, self-heal, and perform biochemical tasks such as sensing or catalysis. The programmable microbial ink concept unlocks the possibility of printing bespoke living systems that combine structural integrity with biological functionality, potentially revolutionizing fields like biomedicine, environmental remediation, and smart textiles.

By harnessing the natural abilities of microbes within a controlled 3D printed scaffold, this technology could lead to sustainable manufacturing approaches where materials grow, adapt, and regenerate, reducing waste and extending product lifespans. It also opens pathways for creating biohybrid devices that merge living cells with electronics or sensors.

Technical Context

The core technical innovation lies in engineering bacteria to secrete protein nanofibers that form a gel-like extracellular matrix suitable for extrusion-based 3D printing. These protein nanofibers are genetically programmed to self-assemble into networks that provide mechanical stability while maintaining cell viability. The ink’s rheological properties are tuned to balance printability and biological function, allowing layer-by-layer deposition without damaging the living cells.

Unlike conventional bioinks that rely on hydrogels or synthetic polymers, this microbial ink is produced directly by the living cells themselves, creating a self-sustaining system. The genetic programmability means the properties of the ink—such as stiffness, porosity, and biochemical activity—can be customized by editing the bacterial strains. This approach integrates material synthesis and fabrication into a single biological process.

However, detailed parameters such as long-term stability of printed structures, scale-up feasibility, and the extent of functional programmability remain areas requiring further research. The interplay between microbial metabolism and structural integrity under various environmental conditions is still being elucidated.

Near-term Prediction Model

This technology is currently at the R&D stage, with promising pilot demonstrations of microbial ink printing. Over the next 12 to 24 months, we anticipate incremental advances focusing on optimizing ink formulations, improving printing resolution, and expanding the functional repertoire of engineered microbes. Early applications may emerge in niche biomedical devices, environmental biosensors, or small-scale bioremediation constructs.

Commercial adoption will depend on overcoming challenges related to regulatory approval for living materials, ensuring biosafety, and demonstrating consistent performance in real-world conditions. Given the complexity of integrating living cells into printed products, widespread commercialization is likely 3 to 5 years away, contingent on multidisciplinary collaboration between bioengineers, materials scientists, and manufacturers.

What to Watch

- Advances in genetic engineering tools enabling more sophisticated control over protein nanofiber production and microbial behavior.

- Development of scalable bioreactor systems for producing microbial inks at industrial volumes.

- Regulatory frameworks evolving to address safety and ethical considerations of living materials in consumer products.

- Integration of living materials with electronic or sensing components to create hybrid devices.

- Demonstrations of living material applications in healthcare, such as wound dressings or implantable scaffolds with active biological functions.

- Research on long-term durability, self-healing capabilities, and environmental responsiveness of printed living structures.

In conclusion, programmable microbial inks represent a frontier in 3D printing that merges biology and materials science to create dynamic, living architectures. While still nascent, this approach promises to redefine material design and manufacturing paradigms by embedding life itself into the fabric of printed objects.